Event Date:

Event Location:

- Hatlen Theater

Event Price:

$17 General Admission

$13 UCSB Student/Faculty/Staff/Alumni, Non UCSB Student/Senior/Child

*The show contains nudity. Please be advised.

- The Chalk Circle

- Synopsis

- The Caucasus

- Director's Note

- Dramaturg's Note

- Interview

- Director

- Playwright

- Press

- Gallery

by Bertolt Brecht translated by Eric Bentley

directed by Simon Williams

Widely considered to be Brecht’s most engaging and humane play, The Caucasian Chalk Circle tells the story of Grusha who sacrifices her happiness and dignity for the sake of an abandoned child she takes as her own. Containing one of the most memorable trials ever staged, this thriller and controversial political polemic is a great classic of the modern theater that you don’t want to miss.

The Chalk Circle: Brech't Interpretation of a Classic Tale

The dramatic climax of the play, Azdak’s judgment over the motherhood of Michael Abashwili, finds its origins in a variety of ancient and modern texts. The motif of the chalk circle first appears in the Old Testament. In the book of 1 Kings, two women appear before the king of Israel, King Solomon, to settle their dispute over the ownership of a baby. The women lived in the same household and had both recently given birth. One woman had lost her infant, and greedily tried to claim the remaining baby as her own. When neither woman would concede, King Solomon declared the fair solution would be to cut the baby in half with a sword and award each woman with an equal share. Rather than see her child killed, the true mother begs King Solomon to save the baby and award it to the other woman, who appears not to take issue with the impending death of the infant. King Solomon justly grants the biological mother ownership of the child due to her selfless and steadfast love.

The Chalk Circle also appears within the Chinese theatrical repertoire in the 13th and 14th centuries. In this variation, a beautiful young woman, Hai-Tang, is sold into prostitution after her father’s death. A wealthy, childless tax collector named Ma Chun-shing takes Hai-Tang as his second wife. Hai-Tang has a song by Ma Chun-shing, which causes the first wife, Ah-Siu, to become jealous. Ah-Siu poisons Ma Chun-shing and blames his death on Hai-Tang. When Hai-Tang is arrested, Ah-Siu claims Hai-Tang’s child as her own so as to inherit their late husband’s fortune. Hai-Tang’s impending execution is interrupted by Judge Bao, who sets up the test of the chalk circle. Drawing a circle on the ground, Judge Bao instructs the two wives to tug the child out of the ring. Hai-Tang, unwilling to hurt her child, allows Ah-Siu to pull the child towards her. Judge Bao deduces that Hai-Tang is the true mother and grants the child to the rightful biological mother.

Brecht found inspiration from these older variations as well as from the 1925 adaptation by the German playwright Klabund. Brecht’s take on the story includes a vital and distinct difference. In The Caucasian Chalk Circle, the kitchen maid Grusha rescues and cares for Michael Abashwili, the abandoned son of the late governor. Throughout her perilous journey, Grusha comes to care for the baby and considers him her own child. When the child is captured by the Ironshirts, Grusha must appear in court to battle Natella Abshwili for custody of Michael. When Azdak, the judge, orders Natella and Grusha to pull Michael out of the chalk circle, Grusha repeatedly lets go, unable to cause Michael any harm. Instead of granting custody to vain Natella, the biological mother, Azdak recognizes that Grusha is better suited to care for Michael and awards the child to her. We see a new kind of motherhood, one based upon love and goodness rather than biology. In true Marxist fashion, Brecht utilizes the pivotal outcome of the trial to reinforce the play’s central moral: “Things shall go to those who are good for them,” rather than merely those who began with the thing in question – land, power, or even a child.

Synopsis

Prologue

From the rubble of war emerge two groups of Caucasian farmers that dispute over ownership of farmland. Despite the land previously belonging to a goat-herding group, the fruit farmers are granted the land due to their grand plans to fully utilize the land’s potential. A Storyteller arrives to perform a parable that illustrates why the decision to grant the land to the fruit farmers was just and right.

Act 1: The Noble Child

On Easter Sunday in war-torn Grusinia, the governor Georgi Abashwili, his wife Natella, and their son Michael attend church. Grusha Vashnadze, a kitchen maid, encounters Simon Shashava, a court soldier. The Fat Prince, capitalizing on the governor’s military struggles, stages a coup during Easter Mass and takes over the city. In the midst of the chaos, Grusha and Simon meet and profess their love, agreeing to reunite and marry after the war ends. Grusha discovers the infant Michael, who has been left behind by his mother, Natella. Grusha takes Michael with her as she flees the burning city for the northern mountains.

Act 2: The Flight into the Northern Mountains

During her journey towards her brother’s house in the mountains, Grusha finds herself pursued by Ironshirt soldiers, sent by the Fat Prince to reclaim Michael. After trying to protect Michael by leaving him with a peasant couple, Grusha recognizes her motherly affection for the baby. When the Ironshirts discover Michael, Grusha strikes one of the soldiers with a log and rescues him from their grasp. Crossing a dangerous bridge over a vast canyon, Grusha risks both her life and Michael’s in order to throw the Ironshirts off of their trail.

Act 3: In the Northern Mountains

Weak from her mountain trek, Grusha reaches the home of her brother, Lavrenti, and his wife, Aniko. Grusha is met with suspicion from Aniko, who questions Michael’s parentage given Grusha’s singleness. Lavrenti searches for a husband for Grusha, hoping a marriage would help disguise Michael as her own child and give them a safe place to wait out the war. An agreement is made to marry Grusha to Jussup, a “dying” man in a mountain village. During the wedding/funeral, Grusha learns that the war has ended and anticipates Simon Shashava’s return. Jussup, having feigned sickness to avoid the draft, miraculously recovers, leaving Grusha in an unhappy marriage. Simon returns to find Grusha married with a child and leaves her distraught, believing their agreement to be broken. The Ironshirts find Grusha yet again and reclaim Michael, taking him back to the city to reunite him with his mother, Natella Abashwili.

Act 4: The Story of the Judge

Returning to the time of the coup, the Storyteller tells the tale of how Azdak, former court scribe, becomes the new judge. Unknowingly, Azdak grants the destitute Grand Duke refuge in his home. Upon discovering his error, Azdak commands Shauwa, a policeman, to take him to the capital for trial. The Fat Prince proposes that his nephew, Bizergan Kazbeki, become the new judge, as the former one has been hanged. Azdak requests to test the nephew’s knowledge of the law through staging a mock trial. Playing the part of the Grand Duke, Azdak cleverly mocks the political decisions and behaviors of the political leaders. He earns the respect of the Ironshirts, who appoint him judge instead. Through a series of trials, Azdak proves himself to be a controversial yet fair judge, favoring the poor rather than adhering to the law and thus upending expectations of power and class.

Act 5: The Chalk Circle

Returning to the present, Grusha waits in the city for the arrival of Azdak, who will determine the fate of Michael. Simon Shashava meets her and offers Grusha his help. Joined by Natella Abashwili and her lawyers, Grusha meets Azdak for the trial. Azdak orders Shauwa to draw a circle on the floor with chalk and has Michael stand in the middle. He instructs both Natella and Grusha to hold onto the child, and declares that the true mother would be able to pull him from the circle and thus would be granted the child. Grusha cannot bring herself to pull on Michael and hurt him, and lets go. In a twist, Azdak rules that Michael should go to Grusha instead, as she is best fit to care for him. Azdak then annuls the marriage between Grusha and her peasant husband, leaving her free to begin her life with Simon and Michael.

The Caucasus: A Land of Diversity and Division

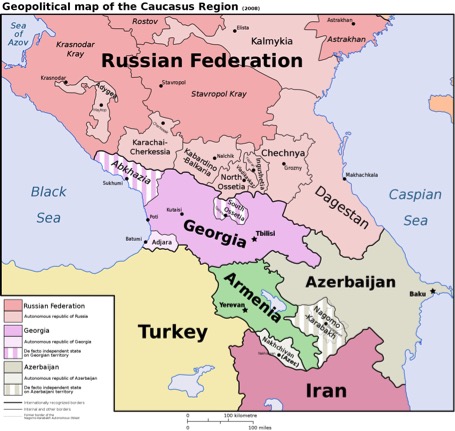

The Caucasus is a land of in-betweens: East and West, Asia and Europe, Caspian and Black Sea, Christianity and Islam, independence and occupation. A vast mountain range divides the Russian-controlled northern regions, including Chechnya and Dagestan, and the modernly independent southern countries of Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The entire region exists in a perpetual state of political upheaval, having been occupied at one time or another by the Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Persians, Arabs, Turks, Mongols, and Russians. This plethora of ruling powers and influences formed the Caucasus into a unique melting pot of language, culture, religion, art, and music. Its varied nature makes it a richly diverse yet polarizing location. Frequent internal clashes over beliefs and customs complicate the identity of the Caucasus and of the many ethnic groups of people that call the region home.

It was in this turbulent location that Brecht chose to set his drama. Its constant upheavals of power, social class struggles, and various cultural influences provided the ideal platform for Brecht’s personal, political reflections on being a socialist German living in exile during WWII. Although the play takes place in a fictionalized version of 19th Century Georgia and Azerbaijan, the situations and tensions found within the dramatic action may easily apply to a variety of times, places, and sociopolitical circumstances. The “in-between-ness” is reflected in every aspect of the characters, society, and situations found within The Caucasian Chalk Circle. A constant state of imbalance and moral grayness permeates every facet of the play and lends itself to the potency of the play’s humanistic questions. What does it mean to be good, especially in times of war and uncertainty? How can justice overcome man-made structures of oppression and inequality? What does it mean to belong, or to own? These questions, among many others, resonate within the text, the world of the play, and the real world from which we view Brecht’s dramatic masterpiece.

Director's Note

My journey to this production has lasted almost 50 years. Back in 1968, I directed The Caucasian Chalk Circle at Pahlavi University, in Shiraz, Iran. It was performed in English and was a transformative experience. Virtually none of the students cast had even seen a play, let alone performed in one, but they took to the whole idea of theatre with immense enthusiasm. Rehearsals were vigorous, exuberant and filled with joy. Furthermore, in the context of Iranian society as it was then, the central message of the play, “What there is shall go to those who are good for it”, had a truly revolutionary ring to it for those who were performing. Sadly, I never saw the final production. The whole project was disrupted by a massive student strike that closed the entire university down and ended with tragic consequences for many students. When the dust had cleared, the production did see the light of day, but by that time I was long gone from Iran and did not see it. This production today is the fulfillment of a long-desired goal.

When I first directed it, The Caucasian Chalk Circle was little more than 20 years old, and due to the immense influence that Brecht’s thought exercised on theatre internationally, it was then regarded as a leading work of the avant-garde. Now it is a classic, as revered as Shakespeare, Ibsen, and the great comedies of the 17th and 18th centuries. But oddly enough, coming back to it in 2017, it seems much more current than it did back in the 60s. The idea that things shall go to those who are good for them seemed fairly self-evident to me in the 60s; it does not now, as we are becoming increasingly aware of mighty inequalities in our own society. Although the 60s had its own raft of troubles, the plight of refugees was not among them; now, we are faced with a worldwide refugee crisis, and Grusha Vashnadze, the courageous kitchen maid, can be seen as emblematic for our time. Above all, we have mostly lived with the assumption that the truth is an objective entity that all of us basically agree upon and respect; now, however, we live in a dangerously “post-truth” age, one that we can perhaps see symbolized in the wildly erratic judge Azdak, who peddles “alternative justices” with flamboyance. But he is not all bad. That the play ends in Azdak happening to achieve an act of perfect justice, thereby rewarding Grusha for all her trials will, I hope, be understood as offering a glimmer of hope to our own conflicted times. What can offer even more hope is that the student cast at UCSB in 2017 has worked with as much optimism, fervor and a sense of our common humanity as their counterparts in Iran did 50 years ago.

Dramaturg's Note

Within the pantheon of epic dramatic writing by German playwright Bertolt Brecht, The Caucasian Chalk Circle stands out from the rest. Brecht wrote his moving and politically charged parable play in 1944 while seeking exile in America. The events and themes of the play are both of a specific time and place, yet The Caucasian Chalk Circle transcends specificity in its depiction of the universal narratives of war, peace, and social class struggle. The world of Caucasian Chalk Circle is both of an imaginative and distant world, and simultaneously here and now. The injustices found within the narrative are not mere dramatic exaggerations; Brecht’s text unflinchingly examines the undercurrent of human corruption that has flourished and reared its ugly head ceaselessly throughout history. Even today. Even here. Even now.

Despite the play’s often-painful portrayal of humanity, The Caucasian Chalk Circle differs from Brecht’s other works in its unique presentation of an optimistic conclusion. War, oppression, and injustice are man-made conditions, and thus may be solved by humankind. However, according to Brecht, such a reversal may only be attempted through re-appropriating power to “those who are good for it,” rather than those who wield power irresponsibly and destructively. Brecht, a staunch Marxist, calls for social reform and utilizes the theatre as an optimal space for inciting change and awareness. Tactics of alienation and self-awareness aim at bringing viewers into the action and then jolting them back out, implicated in the onstage action and grounded in their own realities.

The Caucasian Chalk Circle is not merely a tale of suffering and social reform: Brecht’s beautifully crafted narrative also explores ideas of motherhood, love, goodness, justice, and sacrifice. Grusha, the stubborn and spirited central figure of the play, fights to remain good and just in a world that punishes for doing so. Her journey, narrated in both song and speech, proves that those who sacrifice and suffer for the good of the world – or even for just one person – ultimately survive and inspire others towards unity, reform, and maybe even peace.

Brecht wished his theatre to resonate within the hearts and minds of audiences, and chiefly to entertain. We hope that our production meaningfully examines questions of war, social class, hope and justice through entertaining spectacle, song, and story.

The Brechtian theatre is not a “safe” space. But then again, neither is the world beyond the walls of the stage.

-Elaine Pazaski, production dramaturg

The Interview with the Director Simon Williams

Why did you choose to direct The Caucasian Chalk Circle?

How does The Caucasian Chalk Circle fit into the UCSB Theater/Dance Performance season?

How does The Caucasian Chalk Circe fit with your directing style?

What are the biggest challenges in directing The Caucasian Chalk Circle?

What can you tell us about the cast?

What do the audiences need to know in order to understand the play?

What would you like our audiences to take away after watching the play?

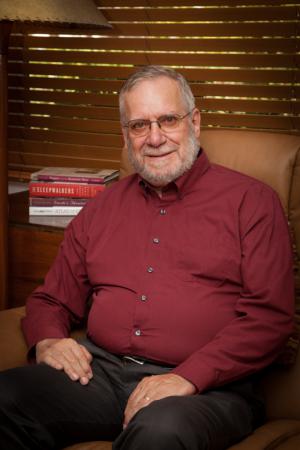

About the Director

Simon Williams is Professor in the Department of Theater and Dance. He has taught at universities on four continents, including the University of Regina, of Alberta, Cornell University and, since 1984, UCSB. He has published widely in the fields of European continental theatre, the history of acting, Shakespearean performance, and operatic history. His major publications include German Actors of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (Greenwood, 1985), Shakespeare on the German Stage, 1586-1914 (Cambridge, 1990), Richard Wagner and Festival Theatre (Greenwood, 1994), and Richard Wagner and the Romantic Hero (Cambridge, 2004). He has contributed numerous articles in his fields of specialty in edited volumes and leading periodicals. He is also an active director and reviewer of opera. His current projects include co-editing A History of the German Theatre for Cambridge University Press and studies of Shakespeare in the eighteenth century and European opera in the nineteenth.

Simon Williams is Professor in the Department of Theater and Dance. He has taught at universities on four continents, including the University of Regina, of Alberta, Cornell University and, since 1984, UCSB. He has published widely in the fields of European continental theatre, the history of acting, Shakespearean performance, and operatic history. His major publications include German Actors of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (Greenwood, 1985), Shakespeare on the German Stage, 1586-1914 (Cambridge, 1990), Richard Wagner and Festival Theatre (Greenwood, 1994), and Richard Wagner and the Romantic Hero (Cambridge, 2004). He has contributed numerous articles in his fields of specialty in edited volumes and leading periodicals. He is also an active director and reviewer of opera. His current projects include co-editing A History of the German Theatre for Cambridge University Press and studies of Shakespeare in the eighteenth century and European opera in the nineteenth.

About the Playwright

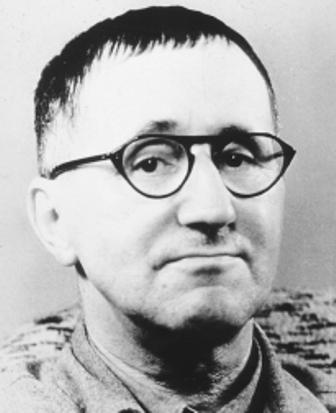

Bertolt Brecht, original name Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht (born February 10, 1898, Augsburg, Germany—died August 14, 1956, East Berlin), German poet, playwright, and theatrical reformer whose epic theatre departed from the conventions of theatrical illusion and developed the drama as a social and ideological forum for leftist causes.

Bertolt Brecht, original name Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht (born February 10, 1898, Augsburg, Germany—died August 14, 1956, East Berlin), German poet, playwright, and theatrical reformer whose epic theatre departed from the conventions of theatrical illusion and developed the drama as a social and ideological forum for leftist causes.

Until 1924 Brecht lived in Bavaria, where he was born, studied medicine (Munich, 1917–21), and served in an army hospital (1918). From this period date his first play, Baal (produced 1923); his first success, Trommeln in der Nacht (Kleist Preis, 1922; Drums in the Night); the poems and songs collected as Die Hauspostille (1927; A Manual of Piety, 1966), his first professional production (Edward II, 1924); and his admiration for Wedekind, Rimbaud, Villon, and Kipling.

During this period he also developed a violently antibourgeois attitude that reflected his generation’s deep disappointment in the civilization that had come crashing down at the end of World War I. Among Brecht’s friends were members of the Dadaist group, who aimed at destroying what they condemned as the false standards of bourgeois art through derision and iconoclastic satire. The man who taught him the elements of Marxism in the late 1920s was Karl Korsch, an eminent Marxist theoretician who had been a Communist member of the Reichstag but had been expelled from the German Communist Party in 1926.

In Berlin (1924–33) he worked briefly for the directors Max Reinhardt and Erwin Piscator, but mainly with his own group of associates. With the composer Kurt Weill he wrote the satirical, successful ballad opera Die Dreigroschenoper (1928; The Threepenny Opera) and the opera Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (1930; Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny). He also wrote what he called “Lehr-stücke” (“exemplary plays”)—baldly didactic works for performance outside the orthodox theatre—to music by Weill, Hindemith, and Hanns Eisler. In these years he developed his theory of “epic theatre” and an austere form of irregular verse. He also became a Marxist.

In 1933 he went into exile—in Scandinavia (1933–41), mainly in Denmark, and then in the United States (1941–47), where he did some film work in Hollywood. In Germany his books were burned and his citizenship was withdrawn. He was cut off from the German theatre; but between 1937 and 1941 he wrote most of his great plays, his major theoretical essays and dialogues, and many of the poems collected as Svendborger Gedichte (1939).

Between 1937 and 1939, he wrote, but did not complete, the novel Die Geschäfte des Herrn Julius Caesar (1957; The Business Affairs of Mr. Julius Caesar). It concerns a scholar researching a biography of Caesar several decades after his assassination. The plays of Brecht’s exile years became famous in the author’s own and other productions: notable among them are Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder (1941; Mother Courage and Her Children), a chronicle play of the Thirty Years’ War; Leben des Galilei (1943; The Life of Galileo); Der gute Mensch von Sezuan (1943; The Good Woman of Setzuan), a parable play set in prewar China; Der Aufhaltsame Aufstieg des Arturo Ui (1957; The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui), a parable play of Hitler’s rise to power set in prewar Chicago; Herr Puntila und sein Knecht Matti (1948; Herr Puntila and His Man Matti), a Volksstück (popular play) about a Finnish farmer who oscillates between churlish sobriety and drunken good humour; and The Caucasian Chalk Circle (first produced in English, 1948; Der kaukasische Kreidekreis, 1949), the story of a struggle for possession of a child between its highborn mother, who deserts it, and the servant girl who looks after it.

Brecht left the United States in 1947 after having had to give evidence before the House Un-American Activities Committee. He spent a year in Zürich, working mainly on Antigone-Modell 1948 (adapted from Hölderlin’s translation of Sophocles; produced 1948) and on his most important theoretical work, the Kleines Organon für das Theater (1949; “A Little Organum for the Theatre”). The essence of his theory of drama, as revealed in this work, is the idea that a truly Marxist drama must avoid the Aristotelian premise that the audience should be made to believe that what they are witnessing is happening here and now. For he saw that if the audience really felt that the emotions of heroes of the past—Oedipus, or Lear, or Hamlet—could equally have been their own reactions, then the Marxist idea that human nature is not constant but a result of changing historical conditions would automatically be invalidated. Brecht therefore argued that the theatre should not seek to make its audience believe in the presence of the characters on the stage—should not make it identify with them, but should rather follow the method of the epic poet’s art, which is to make the audience realize that what it sees on the stage is merely an account of past events that it should watch with critical detachment. Hence, the “epic” (narrative, nondramatic) theatre is based on detachment, on the Verfremdungseffekt (alienation effect), achieved through a number of devices that remind the spectator that he is being presented with a demonstration of human behaviour in scientific spirit rather than with an illusion of reality, in short, that the theatre is only a theatre and not the world itself.

In 1949 Brecht went to Berlin to help stage Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder (with his wife, Helene Weigel, in the title part) at Reinhardt’s old Deutsches Theater in the Soviet sector. This led to formation of the Brechts’ own company, the Berliner Ensemble, and to permanent return to Berlin. Henceforward the Ensemble and the staging of his own plays had first claim on Brecht’s time. Often suspect in eastern Europe because of his unorthodox aesthetic theories and denigrated or boycotted in the West for his Communist opinions, he yet had a great triumph at the Paris Théâtre des Nations in 1955, and in the same year in Moscow he received a Stalin Peace Prize. He died of a heart attack in East Berlin the following year.

Brecht was, first, a superior poet, with a command of many styles and moods. As a playwright he was an intensive worker, a restless piecer-together of ideas not always his own (The Threepenny Opera is based on John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera, and Edward II on Marlowe), a sardonic humorist, and a man of rare musical and visual awareness; but he was often bad at creating living characters or at giving his plays tension and shape. As a producer he liked lightness, clarity, and firmly knotted narrative sequence; a perfectionist, he forced the German theatre, against its nature, to underplay. As a theoretician he made principles out of his preferences—and even out of his faults.

Press

We are proud to say that Noozhawk is our media partner.

“The Caucasian Chalk Circle” is something of a theatrical oddity. Williams calls it one Brecht’s greatest works, but it’s rarely staged. Part of the reason is logistics. Truly an epic, there are 97 parts — UCSB’s production covers all of them with a cast of 26 — and the play includes numerous short scenes that need to flow together.

The play certainly echoes some of today’s political debates about inequality and abuse of power. Williams and his student actors have noted them in rehearsal, “but I don’t want to belabor them,” he said. “I’m sure the audience will be fully capable of picking them up for themselves.”

Gallery

Photo credit: David Bazemore

Photo credit: David Bazemore

Photo credit: David Bazemore

Photo credit: David Bazemore

Photo credit: David Bazemore